"Be Dignified, as a Rule"

by David Cain

"Much of what you’ve read on this blog has been written in pajama pants. Writing directly follows meditation in my morning routine, so I’ve often gone right from the cushion to the coffeepot to the desk. Occasionally life would remind me that there are practical reasons to put on socially acceptable pants before beginning the workday. Someone could knock on the door, for example. But for the most part it seemed like an unnecessary formality that only added friction to the getting-to-work process.

Today I do get properly dressed before going to my desk, because it’s simply more conducive to productivity. Changing into leaving-the-house clothes gives me a “going to work” feeling, which is the kind of feeling you want whenever you’re going to work, even if your office is just across the hall.

Recently I noticed that this effect is stronger the better I dress. Jeans and a pullover are better than PJs and a hoodie. Proper slacks and a button-up shirt are even better. I’m sure an Edwardian waistcoat and tie would generate an even stronger feeling of being a dignified writer getting to work.

I thought it was interesting that this feeling of dignity often follows when you discover a better way to do a thing. Decent pants don’t just inspire a productive mentality, they also elevate the writer’s self-respect. Dusting a shelf after clearing it entirely, rather than by shuffling its contents around, improves the quality of the dusting but also just feels more dignified. Dutifully assembling your tools and ingredients before cooking, a practice known as mise en place, improves the food but also dignifies the cooking process, as well as the person doing it, because you’re no longer scrambling like Ricky Ricardo to find the right spices while your rice boils over.

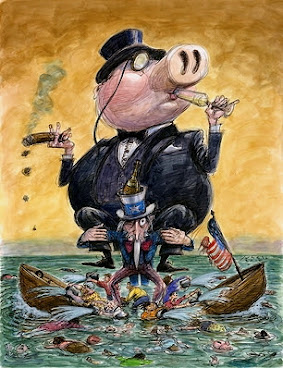

Undignified

It only recently occurred to me that it actually works the other way around. Dignity doesn’t follow effectiveness as much as effectiveness follows dignity. We’re more engaged while reading from a beautiful hardcover than from a computer printout, or in a lamplit armchair rather than a plastic patio chair. Wine tastes better out of a spotless wineglass than from a paper cup. Perhaps we should have dignity foremost in mind whenever we do anything, because it’s an intuitive sense we all have, and it points the way to a thing done well.

It might sound like I’m equating my own aesthetic preferences to dignity. I like lamps and armchairs and wine, maybe you don’t. What feels dignified depends on the person, but we can always sense our own dignity, or lack thereof, in how we do a thing, even when nobody else is there to see it. Dignified doing has always spoken to me, although I haven’t known what to call it. I once wrote a post on Raptitude’s Patreon feed specifically about the dignity of looking up words in a real, paper dictionary — or rather the corrosive indignity of using an ad-riddled online one that you don’t even own.

Exudes purpose There are dignified and undignified ways to do everything. You might have noticed a subtle difference in how it feels to gently push a jar onto a crowded fridge shelf, forcing the other jars back and to the sides, and how much better it feels to make a space intentionally and then put the jar in it. A little more intentionality, a lot more dignity.

Technology tends to pull us away from this way of being, eroding dignity in the quest for speed, variety, or convenience. I find it more dignified, for example, to listen to music by playing a single album, rather than an AI-generated playlist. Instead of an infinite stream of algorithmically-similar songs, you get a coherent work as its artist intended. I have no vinyl collection, but anyone who does knows there is something spiritually superior about setting an LP onto a turntable rather than thumbing over to the same album on Spotify, sound fidelity aside.

I’m sure some proportion of our modern malaise comes from this sort of technology-induced dignity loss. The more our tools automate once-manual actions, and the more we access them all through the same lifeless touchscreen, the less intentionality and resolve there is behind whatever we’re doing. Maybe some friction and formality is a good thing, because it keeps our values in charge of the action, leaving less to momentum.

Ultimately it’s a choice though, and the dignified way is there whenever you look for it. I have a folding steamer basket I use almost daily. For a while one of the petals would come off if you held the thing sideways, so I made sure to handle it gingerly and keep it level. Finally I did the dignified thing: I got out a flathead screwdriver, sat down at the table, and carefully re-bent the metal flap that held the loose petal in place. Now it stays. The steaming of vegetables is a little easier of course, but the greater gain was in becoming the person who fixed the thing that needs fixing, and no longer the person oppressed by his faulty steamer basket.

Dignity isn’t only a matter of the tools, clothing, or the method with which you do a thing. It’s in the way of doing: the earnestness, the uprightness, the respect for the task and its doer. I’m endlessly inspired by a particular entry in Marcus Aurelius’s journal, in which he admonishes himself to do everything this way, to “do what comes to hand with a correct and natural dignity,” and to regard this way of being as the only thing the gods require of him.

Dignified to the end.

There have been periods, lasting hours or sometimes days, when I’ve settled into this dignified groove of doing one thing at a time, with undivided intention, devoting the whole self to each task, rather than applying just “enough” of the self to deal with it.

The sensation of being in this groove is like a calm version of surfing - you’ve caught a certain exhilarating momentum, you have to make frequent, intuitive adjustments to maintain it, and the roiling sea still surrounds you, but there’s no thought whatsoever of wanting to be anywhere else."